Tea, Chops and Time

Published: Kerb 32 – Unsaid

Authors: Greg Grabasch, Joe Bean, Holly Farley

Greg Grabasch:

I guess not all journeys lead to contemplation of life’s mysteries, but as we gather around, our cups of tea, chops in hand, we enter a space of profound connection. Gently slowing our pace, we become more attuned to one another, our senses sharpening as we wait and listen. In these moments, we focus on the needs of others, serving, settling, and ultimately, truly listening.

We may consider these gatherings offer a rare opportunity to tap into a collective consciousness that transcends individual experience. They are moments in time and in place where we plug into a shared awareness, becoming more sensitive to the world around us and the individuals who comprise our small collective.

Contemporary discussions surrounding the philosophies of Pan Consciousness and Fine-Tuning, championed by thinkers like Phillip Goth and Paul Davies, prompt us to ponder the fundamental questions of existence. Pan Consciousness explores the interconnectedness and consciousness that may permeate all of existence, while Fine-Tuning philosophy delves into the apparent design and orderliness of the universe.

David Chalmers Australian philosopher and cognitive scientist poignantly notes, “Consciousness is not just the sum of all the information processing that goes on in the brain. It also includes the ability to experience feelings, sensations, and emotions.” This sentiment underscores the depth of our shared experiences and the profound nature of our collective consciousness.

The simple act of coming together to share tea and chops, with the intention of fine-tuning our lives for the better, offers a glimpse into the purposeful evolution of the universe. Through collective listening and being present with one another, we create the conditions for positive ongoing change. These gatherings transcend mere social interactions—they become a means of personal and collective transformation.

In these moments of connection, we realise the importance of cherishing our shared experiences and embracing the opportunities for growth they afford us. They remind us to contemplate the broader implications of our interactions, respecting the lived experiences that shape our understanding of the world, and our precious time and place within.

Joe Bean

If there is a collective consciousness, we, humans, are dominating the airwaves. There’s no way we are tuning in to the diverse frequencies of the natural world, the languages, behaviours and processes we can’t easily grasp. We aren’t listening, and so the ‘unsaid’ goes unheard.

We must strive to listen more carefully and understand more. In our work we do this with humans through listening - through tea, chops and time. It can be tricky, but with more-than-humans, it gets trickier. The other day we threw a chop into the water with an Australian Giant Cuttlefish community we are working with in Whyalla and they tried to mate with it. We couldn’t figure out how the lesser long eared bats at Koonalda Cave on the Nullarbor liked their tea.

The only tool we find ourselves left with is time. It’s fun to seek out species other than humans in our day-to-day lives, meeting them on their terms and with patience. Try it – see if the swallow community in the dunnies down the beach wants a bar of you. Try again tomorrow if they don’t. Revisiting a platypus in the South Hobart Rivulet near my place, peeking over the bridge railing, I notice that the platypus seems to politely ask ‘can you sort out the rubbish tip up the road?’ every time it gets a bit of twine wrapped around its neck.

Our consultancy work doesn’t have this luxury of time, often limited to a cycle of three-day site visits to regional and remote areas. When considering visitor upgrades for Noorook Yalgorup, a threatened ecological community of Thrombolites at Lake Clifton, our client would have been baffled if we insisted that we sat around in camo for a few months to see if we could work out what the snakes thought of our concept plans. So we learn what we can from small immersions and interactions with these ecological systems, and turn to time spent by others to begin to grasp what might be going unsaid.

The obvious one is time spent by experts. We speak to government scientists, consult management plans and guidelines (publications like DCCEWS’s ‘Light Pollution Guidelines for Wildlife’ are absolute corkers) and read widely to give ourselves the best chance of understanding the technical aspects of what a species requires. There are special, perspective altering texts out there that have influenced our practice - ‘An Immense World’ by Ed Yong and its exploration of ‘umwelt’ (the unique sensory world of every species) is one example. We drew upon all of this when considering how any security lighting near the entry of Koonalda Cave might wreak havoc with the lesser long eared bats roosting there. We remind ourselves, though, that in many cases this formal expertise might also come from limited time – field trips, the small immersions of professionals from elsewhere, just like ourselves.

We believe the less ‘formal’ expertise garnered from lived experience has superpowers. The intuition and the lived experience of the passionate local – be it forager, tour guide, artist, diver, gardener – is invaluable to our projects and we respect it immensely. This is the type of ‘informal’ knowledge that is passed down generations by those bearing witness and tuning into other frequencies over the years, decades, centuries and millennia. In Whyalla, it’s the Barngala Traditional Owners and local fisherman and divers. They tell us old stories, point out gaps in the data, review our developing plans against their experiences, and explain what happens underwater on those weeks where it’s so cold they put on two pairs of socks. Through this we get an idea of the behaviours and incremental changes of a system that we wish to learn from and support.

When the Giant Cuttlefish are too busy mating to attend our workshops, we can turn to local heroes who advocate for species other than themselves. This lived experience provides a kind of interspecies imagination that teaches us to design with empathy and care when we are newcomers to precious places, and equally makes us more observant of the needs of the platypus when we return home. Through what we learn from these people, we cannot emphasise enough the importance of the diversity of frequencies through which the natural world is speaking to us, and the value of helping to amplify it.

Holly Farley

For too long, we—designers who reflect the dominant culture and intersecting identities—have been designing within the extent of our own knowledge and skills. Using our knowledge and professional skills to create environments that reflect us, with some small inclusion for accessibility and, more recently, Country. However, as Mother Nature and folks worldwide scream, it’s clear operating within the bounds of our own knowledge is failing us.

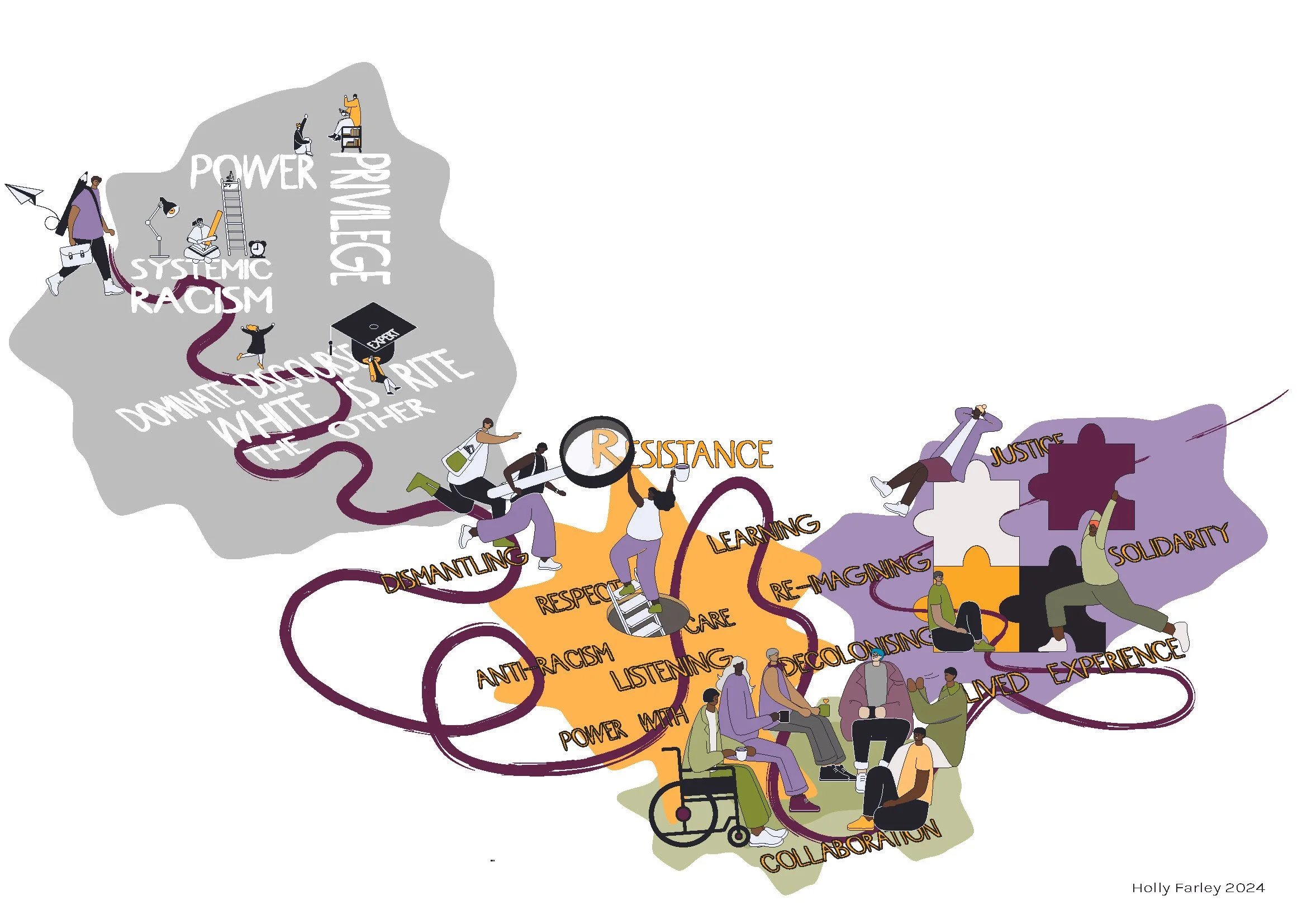

It seems we, white folk, have lost some important knowledge and skills in our hunger for power and privilege. The knowledge and skills required to sit with humility, to truly listen, learn and support the expression of diverse ways of knowing, doing, being and becoming. The skills necessary to foster human connection across socially constructed divides. My question is, are we brave enough to resist, deconstruct and dismantle the dominant modes of knowing, doing, being, and becoming—West is best, and White is right—and move to a position where we can collaboratively reimagine ways of co-creating? To shift from power over to power with.

Design education teaches us that by our own hands, we create. We hold the pen (or mouse); we hold the power. We draw the lines; the lines transform into physical elements on stolen land. We learn discipline-specific information and skills through formal education and configure these learnings through our identities. Developing individual design practices that conform to and/or resist the dominant culture’s norms. We learn to embody the associated and accepted Western ways of knowing, doing, being and becoming – we become experts. In understanding ourselves as experts, we subsequently privilege, value, and trust the information of other experts. Folks just like us who have been legitimised by a system founded on individualism, transaction and power. But what about the expertise that isn’t ‘legitimised’ by a university certificate or a fancy job title—expertise so rich it could change how we understand a place or have the multi-generational knowledge to solve problems Western colonial systems perpetuate?

This isn’t to say experts with discipline-specific knowledge aren’t required, valuable and necessary, but to highlight that when we privilege ‘expertise’ over all else, we inherently exclude folks and uphold systems of harm. We maintain the Western colonial status quo. Consistently, we (sub)consciously learn what and whom to value. To shift from the dominant modes of knowing, doing, being, and becoming, much head and heart learning is required.

The first step in reimagining requires us to learn and articulate how we know, do, be, and become. We need to know and fumble with our own intersectionality, power and privilege, and the systemic context before inviting folks to sit with us to embark on a journey of multiway learning and co-creating. Without a process of learning and systemic change, we are just bleaching things through to the oppressive system we (un)consciously work in and uphold. We can’t resist what is so pervasively unsaid – whiteness– if we don’t learn how to see and hear it.

We need to take the time to (re) learn and practise the skills of human connection—the skills inextricably linked to our collective humanity. The skills of sitting together, hearing the unsaid, and enabling collective understanding and decision-making. Imagine a design workshop where we focus just as much on a project as enjoying a laugh over a chop the consistency of boot leather. Or where we spend a significant amount of time designing engagement experiences so folks feel safe enough to participate and contribute in ways that they feel comfortable.

As designers of the physical environment, these moments require our time – the chops, the cups of tea – sitting together, hearing with our whole being, heart and mind open. Then, maybe, we can be part of a process that begins to co-weave a tapestry of expansive, diverse knowledge that moves us in a direction where we can collectively reimagine environments and systems. .